PHOENIX — Fresh off losing a campaign for sheriff, Pinal County Supervisor Kevin Cavanaugh (R) voted “under duress” in August to certify the county’s primary election results.

This week, he threatened to sue the Arizona county that employs him, claiming — much like President Donald Trump did after his 2020 defeat — that the election had been rigged against him. In a formal notification signaling he intends to pursue a legal claim, Cavanaugh alleged that the Republican county recorder and five other election officials conspired to “modify the results” of the July 30 primary election.

Cavanaugh’s board term does not end until the end of the year, so he will play a role in certifying the general election results, including the presidential race. Cavanaugh has said he will fulfill his duty to accept those results, but his handling of his own loss worries county and state election officials.

Cavanaugh lost his primary race for sheriff by a 2-1 margin. He did not go to court to try to contest his defeat. Instead, he is putting county officials on alert through a “notice of claim” — a precursor to a lawsuit typically used by people who have suffered harm caused by government institutions — that he may sue the county for his electoral loss. In doing so, Cavanaugh is opening a new front in this battleground state in how those skeptical of election outcomes can work outside the traditional court system to try to prove their alleged claims of election interference, election experts and lawyers said.

“We’re trying to put out fires, but the arsonist is in our house,” said one person familiar with the sentiments of county officials about the claim, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to speak candidly. “He’s using his seat of power to undermine elections to undo all the good we’ve done to try to restore faith.”

Cavanaugh did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The previously unreported claim escalates a weeks-long dispute between Cavanaugh, the recorder and the rest of the county governing board about the accuracy of the county’s election systems. Those systems, like elsewhere around the nation, have been strained by misinformation, public records requests filed by fraud-hunting citizen groups and candidates unwilling to accept their losses.

Cavanaugh’s claim is certain to draw even more concern about how the once-sleepy county southeast of Phoenix will approach problems — real or imagined — that could arise during the November general election.

Like in many other conservative rural areas across the nation, Pinal County leaders have been trying to restore the public’s trust in elections and the people who run them after a string of election controversies caused by mistakes and the spread of false information. It’s a job made even more difficult, Pinal officials said, when one of their own is spreading unproven information that they worry could further fuel doubt.

Barry Burden, a political scientist at the University of Wisconsin at Madison and director of its Elections Research Center, said Cavanaugh’s title could bring legitimacy to the notion that election officials are conspiring to falsify election outcomes. And the claim comes just as many voters are beginning to pay attention to the coming election, Burden said.

“It’s about weaponizing a debate about the election — which is not a serious debate — for some other personal goal,” Burden said.

Even before the primary and long before all votes were tallied, Cavanaugh tried to undermine the county’s election systems by asserting, among other things, that election officials had already begun counting — and then publicly discussing — early results. County officials have previously said that was untrue. In Pinal, election workers can begin counting early ballots before Election Day, but the tallies from individual tabulating machines are not aggregated until Election Day. Those combined counts are not known by election officials until after polls close. Cavanaugh also alleged unverified mathematical anomalies that he described as evidence of widespread wrongdoing.

Though Cavanaugh joined his colleagues to certify the county’s election results during a raucous Aug. 13 public meeting, he seemed to convey that he was being coerced into doing so. Two supervisors from a county in southern Arizona were indicted last year after delaying certification of the 2022 election results.

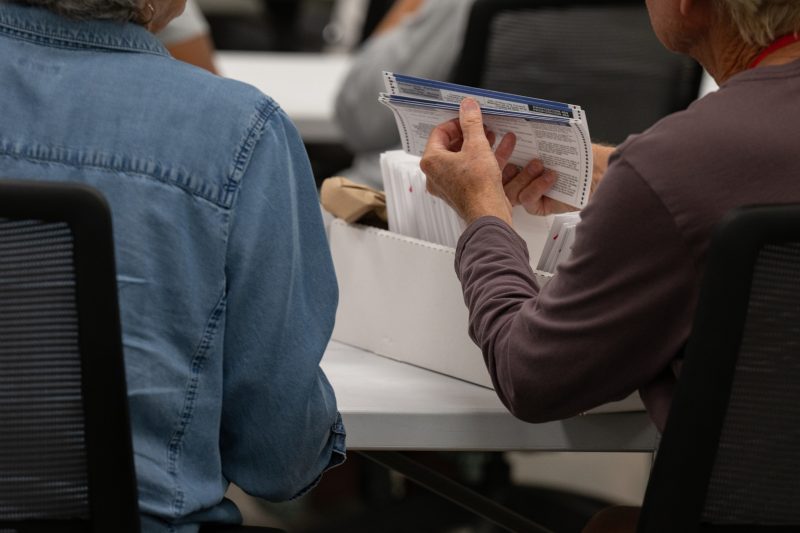

Seeking to assure the fast-growing county’s 425,000 residents that they could trust the election system, Pinal officials hired independent experts to review certain processes of the primary election. The review includes an “election and cybersecurity technical assessment” of some equipment, officials said. It should be completed in October.

“When one member of the Board (of Supervisors) continues to make unfounded allegations, doubt can spread and negatively impact community confidence in our elections process,” Supervisor Jeffrey McClure said in a statement earlier this month.

In the notice this week, Cavanaugh claims that election officials participated “in a coordinated effort” to “transfer approximately 35% of votes” through USB sticks. Those votes, he claimed, were taken from him and given to his GOP opponent, Ross Teeple, who won the election.

Teeple said the election results were accurate and that Cavanaugh’s fraud claims are “insulting to voters and election workers.” The chair of Arizona’s Republican Party, Gina Swoboda, said in an interview that she saw “nothing to suggest that there was any issue with the proper tabulation of the results in any contests.”

In his claim, Cavanaugh said “Pinal County has a duty to operate fair elections wherein a candidate has an expectation that the efforts they make in an election could result in winning, and that the candidate receiving the most votes will win the election.”

He wrote that he would settle his claim for $65,000 if it was resolved by the end of the year, an amount that included attorney and campaign expenses. If the county does not settle by then, he wrote, he would seek more than $1 million, a number that includes the lost value of two full terms — or eight years — of sheriff pay and benefits.

A Pinal County spokesperson, the Republican county attorney and the other Republican members of the governing board declined to comment on the notice of claim, citing potential litigation. The county has 60 days to respond to the allegations; it could deny the claim, ask for more information, offer to settle it or take other action.

Pinal County Recorder Dana Lewis (R) said she is confident in the system and is focused on preparing for the general election.

“We will let the experts complete their assessment of the primary election and do so with confidence in the integrity of the primary results, as reported and unanimously certified by the Pinal County Board of Supervisors,” she said.