Amid calls for him to end his candidacy, President Biden faces twin challenges: He must publicly show that he has the physical stamina and mental sharpness that were visibly lacking in the Atlanta debate. He must also demonstrate to alarmed Democrats that he has a viable path to victory.

In the week since his disastrous debate performance, he has done neither. If anything, he has gone backward.

On Wednesday evening, Biden and Vice President Harris met with Democratic governors in what was a listening session and a show of resolve. One attendee described the meeting as both blunt and productive, but added, “It should have happened last Friday,” the day after the debate.

That same day, according to words attributed to him, Biden told campaign staffers, “No one’s pushing me out. I’m not leaving.” White House press secretary Karine Jean Pierre said Biden is “absolutely not” dropping out.

“We’re going to win this election,” Biden said in an interview that aired Thursday on a Wisconsin radio program aimed at Black listeners. “We’re going to just beat Donald Trump like we did in 2020.”

Biden’s family is resolutely behind him, determined that he stay in the race. His staff continues to prepare a schedule of events while trying to hold back the tides of criticism. For now, the reelection campaign continues. But it continues in crisis mode.

Many Democratic strategists paint a dire portrait of the road ahead. Some of them see no viable path to victory for Biden. Privately, many elected officials, donors, strategists and others think he should quit the race. A few have said so publicly.

Biden is under extraordinary pressure to perform Friday, when he holds a campaign rally in Madison, in the must-win battleground state of Wisconsin in one of the bluest corners of the country, and sits down for a one-on-one interview with ABC’s George Stephanopoulos that will be broadcast as a prime-time special.

The president entered last week’s Atlanta debate narrowly trailing former president Donald Trump in national polls and further behind in several battleground state polls. Polls released Wednesday by the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal show him falling further behind since the debate. The New York Times-Siena College poll found that 74 percent of registered voters think he is too old to serve as president.

Biden campaign officials say their internal surveys show less overall slippage, but they are not blind to his predicament. They knew that the minute Biden faltered in the opening of the debate that what was already a challenging race had become significantly more difficult.

Biden knows that as well, given his decades in politics. But he has failed so far to do what is needed to help his case — at a time when all eyes are on him, when his supporters are looking for evidence that his debate performance was just “a bad night,” and as Biden has been barely visible.

On Monday, the Supreme Court ruled in one of the biggest cases of this term, saying that presidents have immunity from criminal prosecution for official acts. The decision was a victory for Trump, who had brought the issue to the courts by claiming absolute immunity for his actions that led to the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

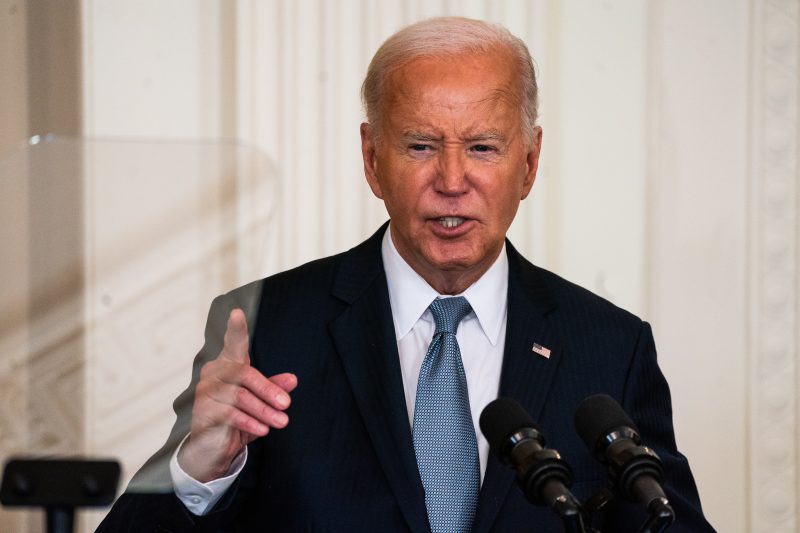

The decision was also an opening for Biden to highlight one of the central issues of his campaign, the preservation of democracy and the rule of law. “The American people,” he said that evening from the White House, “must decide if they want to entrust the president — once again, the presidency to Donald Trump, now knowing he’ll be even more emboldened to do whatever he pleases whenever he wants to do it.”

Biden, however, spoke for just four minutes and answered no questions. The next night, he attended a fundraiser in McLean, Va., where he spoke for fewer than 10 minutes and again took no questions. Other public events this week have included a briefing on extreme weather Tuesday and a Medal of Honor ceremony Wednesday.

Immediately after the debate, Biden’s team appeared successful in tamping down calls from Democratic elected officials for Biden to quit the race. Campaign and White House officials worked the phones last weekend, pleading with allies to hold their fire, despite calls for his withdrawal from some prominent columnists and commentators. Their argument was that any alternative course, such as an open convention, would produce chaos and perhaps even worse odds of winning the election than sticking with Biden.

Biden helped his own cause in those post-debate hours. At a rally the next day in North Carolina, his voice was strong and his energy level was up, both contrasts to the debate. Had that rally been a prelude to a series of such events, it might have worked. But the rally was a one-off, and Biden then retreated from public view. By early this week, the anxiety levels inside the party began to rise appreciably and calls for him to drop out, some private and some public, increased.

In North Carolina, Biden addressed the age issue more directly than in the past. “I don’t walk as easily as I used to,” he said. “I don’t speak as smoothly as I used to. I don’t debate as well as I used to. But I know what I do know. I know how to tell the truth. I know right from wrong. And I know how to do this job. … And I know like millions of Americans know: When you get knocked down, you get back up.”

At different times this year he has tried to address the issue of his age, sometimes with humor, sometimes as he did after the debate. He has never been consistent in dealing with the obvious signs of aging. Now he has no choice. He must address it, and not just with words but also with sustained activity.

At his fundraiser in McLean, Biden blamed his debate performance on jet lag from overseas travel he did in June. “I wasn’t very smart. I decided to travel around the world a couple of times, going through I don’t how many times zones. I didn’t listen to my staff. And then I came back, and I nearly fell asleep onstage.”

He did make two trips to Europe in early June, and after the second trip flew from Italy to California, a span of nine time zones, for a fundraiser with former president Barack Obama. But then he returned to the East Coast for 11 days of rest and preparation before the debate.

Democratic governors pressed him Wednesday to be more visible and vigorous, with some warning that he would have trouble winning their states. They also told him that simply raising the specter of another Trump presidency and the potential damage that could bring to democratic institutions and the country wasn’t sufficient to win. “The governors said you’ve got to have a compelling vision,” said one person who was in the room.

The president has a limited amount of time to demonstrate that he has the capacity for the rigors of the campaign and, not incidentally, for another four years as president if he wins in November.

More events are on his schedule later this week, including the Stephanopoulos interview. But allies say one TV interview is a fraction of what he will have to do to show his ability to handle unscripted situations. Governors told Biden they want to see much more.

“They’ve got to take the chance,” said one governor who attended the meeting. “I’m adamant about this. Do the town hall and take the questions.”

Biden has been making calls to party officials and other allies. One call Tuesday was to Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack. They did not talk about politics.

“He asked about the reason for high beef prices for American families,” Vilsack said. To the Cabinet official, this was a sign that, despite the torrent of criticism aimed at the president, Biden is “doing his job.”

Part of that job now will be to decide whether to stay in the race or get out. Biden might sound defiant and resolved, but he is also having to weigh what is the wisest course. He knows he doesn’t have much time to prove to his party that he can lead it effectively through the closing months of the campaign — and to the voters that he is fit to serve another four years.

Those who have known him longest say that he will make that decision based not on what others tell him but on his own analysis — and not simply personal ambition or vanity.

“I am very confident in this,” Vilsack said, “that whatever decision he makes about his country and the country’s future will be based on what he believes will be in the best interest of the country.”